What’s with the Cross?

In the three thousand words or so below, you’ll find my long-gestating attempt to grasp why Jesus allowed Himself to be crucified and how His crucifixion achieved those aims. Or at least, you’ll find most of it: I cut the writing short. That’s because when it comes to disciplined, long-form argumentation, I may be the slowest writer I know. (Hence, despite a love for knowledge and understanding, I never pursued a PhD and probably never will.)

I typed the first word of what you’ll read below sometime in October 2022. As of the writing of the words of this paragraph, it’s late August 2024. At the rate I’ve been going, to get all my ideas out onto the page would take me another year. Yet every minute I spend writing this essay is a minute not spent relating directly to people or indulging my other expressive hobby, making music, which seems like I’ve all but ignored this entire time. I want to get back to that stuff, especially as both my kids are now in high school and my time with them living full-time under my roof is running short.

The good news with regard to the essay is I don’t think I would have allowed myself to cut it short unless I felt I’d at least managed to grasp the goals and mechanisms of the Cross in my mind. I think I have managed that, so the concepts that remain unwritten at the truncation point I will attempt to put in writing as a sketchy, bulleted, slapdash afterword. The essay starts with the double lines immediately below and is truncated by another pair of lines further down. If you feel you lack the time to read a 35-minute essay or listen to its 50-minute audio version, I begin the afterword with a synopsis of the complete thesis.

- To what ends did Jesus subject Himself to crucifixion?

- How did His subjection to crucifixion accomplish those ends?

- How exactly does any of this demonstrate God’s love for us?

For at least the past fifteen years, cogent answers to these three questions have escaped me. The Cross is obviously an important part of Christianity—the core of it, at least as I was taught—yet at some point along my way, I lost comprehension of its aims and means. Greater love has no one than that he lay down his life, yes…but if I can’t make out a reason for the sacrifice, it’s hard for me to accept gratefully.

Jesus’ crucifixion has become to me like if I were out walking one day near a railway with my brother and my dad, and I notice my dad whisper something in my brother’s ear as a freight train approaches. I see my brother give a solemn nod of acknowledgement, as if what my dad has whispered was instructions. As the train is about to rumble past, my brother steels himself, jumps onto the track, and shouts to me “This is the plan!” just before the locomotive impact kills him. Then my dad turns to me and says, gravely, “That’s how much I love you.” Bewildered, I squint and shake my head quizzically, stuttering in reply, “Couldn’t you have just given me a big hug?”1

Love entails some kind of intelligible benefit to the beloved. Mere dramatic action does not love make. So what was Jesus up to?

My perplexity about the reasons and mechanisms of Jesus’ sacrifice lingers despite hours of conversations with friends on the subject and at least as many hours of reading: Anselm, Fleming Rutledge, Eleonore Stump, N.T. Wright, J.I. Packer, C.S. Lewis, Brad Jersak, Greg Boyd, Gene Edwards, Richard Beck, various acolytes of René Girard, and a gazillion other bloggers. I even corresponded briefly with Boyd about a the Christus Victor model of the Atonement back in 2008–2010.

Those hours of conversation and reading have covered these seven different theories of the Atonement and then some. But I’ve remained unimpressed and, more importantly, unattached to any of them because I don’t find them logically or emotionally compelling and I don’t see them as scripturally thoroughgoing. Absent that, the Eucharist / Lord’s supper / communion has become, for me at least, an awkward, poorly understood adjunct to church life, a tradition whose biblical meaning is slipping away.

But I want the memory of Golgotha to speak to me. I don’t want to go through another Good Friday wondering why Jesus died.2

Hence, below I’ve undertaken an attempt to supply my own answer.

I won’t presume to be writing anything below that hasn’t been written before. But I will promise to provide as logically sound and thoroughly biblical an answer as I can. To help me satisfy the biblicality criterion, here is every New Testament verse I could find that makes what seems to me unequivocal reference to the Cross and affords any sense of Its aims or mechanics, and here are four excerpts from the Hebrew Bible whose echoes I hear in the New Testament writers’ thoughts on the matter. I hope to incorporate every single one of these various texts into my answer.

To satisfy the logicality criterion…well, please let me know how I do.

The first thing that jumps out to me as I read through the catalogue of scriptures is going to sound like a pair of factoids: First, of the eight mentions of the Crucifixion in Acts, in only one of them is the Crucifixion mentioned in isolation from the Resurrection. Second, Acts is the only book of the Bible written by a Gentile (Luke) to a Gentile (Theophilus) largely about Gentiles. Even its narrative hinge is the decision not to require Jewish practice of Gentile converts.

Why point out these details? First, I find them reassuring: Me being a Gentile like Luke and Theophilus, I take comfort in Acts’ relative coyness about presenting Christ crucified without also mentioning Christ resurrected; I take it to mean that I’m not the first goy to whom the Cross by itself risks sounding like “foolishness,” as Paul wrote in another address to a largely Gentile audience.

Second, and more in answer to my questions, this observation about Acts makes it easy to see the simplest of the goals for which Jesus died and how the Crucifixion “works” to that end: Jesus’ death served as a chronological prerequisite for His resurrection. He couldn’t be resurrected until He had died. Jesus Himself states this pretty plainly in John 10:17: “I lay down My life so that I may take it back.”

It isn’t too far a leap to read a second reason in Luke’s almost invariable mention of the Resurrection next to the Crucifixion: The Father raised Jesus from the dead to validate Him as “both lord and Christ” (Acts 2:36)—that is, Jesus subjected Himself to execution so He could be miraculously authenticated as the Messiah by His resurrection.

Acts isn’t the only place where the Cross-Resurrection combo is held up as evidence of Jesus’ lordship like this. Jesus offers this crucial pairing of events:

- in all three Synoptics as the only sign from heaven—the “sign of Jonah” (Matthew 12:39, Matthew 16:4, Luke 11:29-30)—that He’d give to some people, and

- in John as a sign of His authority for clearing the temple.

And even without considering the Resurrection, the Crucifixion can serve as a sign of Jesus’ special status. As Jesus says in John 8: “When you lift up [i.e., crucify] the Son of Man, then you will know that I am [the Light of the world and sent from above]…” How? The New Testament gives us three ways:

- by Jesus having predicted the Cross,

- by the paranormal happenings accompanying the Cross: the darkness, the torn veil, the earthquake, and the apparition of saints, which prompt the watching Roman guard to say, “Truly this was the Son of God!” (or at least, in Luke, to proclaim Jesus an innocent man), and

- by the Cross “fulfilling” the Hebrew scriptures.3

So right away that’s two easily apprehended, biblically stated purposes for Jesus to have subjected Himself to execution, both with clear mechanisms: First, the Cross established the basic temporal precondition for the Resurrection and second, in being accompanied by prophecies, special effects, and the Resurrection itself, the Cross attests to Jesus’ messiahship.

How do these two divine motives for Jesus’ self-subjection to crucifixion demonstrate God’s love for us?

For the first, we could easily argue the Resurrection is how Jesus “through death…frees those who through fear of death were subject to slavery all their lives,” as the writer of Hebrews puts it. Emancipating people from death anxiety and the resulting captivity to sin is certainly an act of love that redounds to the genesis of love in its beneficiaries. For the second, it’s similarly easy to argue that if Jesus is in fact the Messiah, as the signs attending His crucifixion indicate, then it was loving for the Father to have employed those signs to tell us so, especially because this messiah is “gentle and humble in heart,” promising “rest for our souls” (Matthew 11:28-30).4

At this point we’ve incorporated thirty percent of the biblical quotations germane to understanding the why, the how, and the how-is-this-love? of the Cross. Yet neither of the divine reasons for the Crucifixion we’ve dug up so far manage to link it to God’s love directly. According to Paul, God demonstrated His love for us in Christ dying for us. I’ll return later in the essay to the two Resurrection-related love connections I outlined above, but first I want to work toward finding God’s love in Jesus’ death itself, not merely in what followed or accompanied it.

This impulse is amplified by the following: While I find it easy to imagine myriad alternative ways for Jesus to have been validated as Messiah that wouldn’t have involved his public execution, including, say, resurrection appearances after a hypothetical death by natural causes, Jesus seemed quite firm that things had to happen by way of His being killed, as did Peter and Paul. Why?

One way of answering that is to say simply that His Dad told Him to. At least three different New Testament authors seem to say that Jesus’ suffering and crucifixion demonstrated Him perfectly obedient to the Father and thus qualified Him as Messiah, in what His early followers probably saw as fulfillment of Isaiah 53:12.

But to answer in this way is to kick the love can down the road: Putting Jesus through mere ordeal is no way—or at least no self-evident way—for the Father to indicate His love for us—or His love for Jesus, for that matter. God is love. Everything He does is love. So what was the Father’s loving reason to bid Jesus subject Himself to crucifixion?

An umbrella answer to this question goes like this: The Father bid Jesus give Himself over to death in fulfillment of part of “the Law and the Prophets,” and by this I mean “fulfill” in ways more substantial and loving than the mere coming to pass of Old Testament predictions. Jesus points to this idea when He tells the hearers of the Sermon on the Mount, “Do not presume that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish, but to fulfill” (Matthew 5:17).

The fundamental constituent of this fulfillment—and this is not news to me—is that Jesus’ self-surrender permanently and justly provides for the forgiveness of our sins against God per Leviticus 4–6 and 16 by way of Isaiah 53:

- Leviticus codifies the offering of slaughtered animals as a means of dealing with the sins of the people of Israel;

- Isaiah strongly suggests the substitution of a man for these animals;

- Jesus was that man.

(I define forgiveness, by the way, as dismissal [of sin] as a reason for anger, resentment, or requital. I do acknowledge that whole books have been written and could still be written on the subject.)

It’s in the ninth chapter of Hebrews (and all over Hebrews, really) where we find the most elaborate and explicit New Testament callback to Leviticus as an explanation of the import of Jesus’ crucifixion. But it’s not just there. Consider the torn curtain that Matthew, Mark, and Luke report. Consider also John the Baptist’s claim that Jesus was “the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29,36). Moreover, you can hear clear echoes of the Day of Atonement and the guilt and sin offerings of the Law in the New Testament’s sixfold use of the words hilaskomai (“to make atonement for, to have mercy on”), hilasmos (“atoning sacrifice, means of forgiveness”), hilasterion (“atoning sacrifice, mercy seat”), forms of which appear thirty-five times in the Greek translation of Leviticus 4–6 and 16 contemporary to New Testament writers (i.e., in the Septuagint).

As for Isaiah 53, New Testament writers apply direct, partial quotations of it to Jesus or to people’s responses to Him frequently:

- Paul and John both lift at least a part of verse 1,

- Matthew lifts part of verse 4,

- Peter lifts parts of verses 5 and 6, as well as part of verse 9, and

- Luke reports Jesus applying part of verse 12 to Himself as well as Philip applying verses 7 and 8.

Those are just the direct citations. All four Gospel writers tell of Jesus’ silence before Caiaphas and Pilate, which evokes Isaiah 53:7 (“like a sheep that is silent before its shearers, so He did not open His mouth”). All four Gospel writers tell of Joseph of Arimathea, a rich man, taking care of Jesus’ body and donating his tomb to Jesus, which evokes verse 9 (“He was with a rich man in His death”), as does the very ignominy of the means of Jesus’ execution and his therefore likely gravesite if Joseph had not intervened (“His grave was assigned with wicked men”).

Finally, ponder how the idea that Jesus underwent crucifixion to play the part of the Isaiah’s Suffering Servant and thus stand in as the ultimate guilt and sin offering illuminates other, less precise New Testament claims that Jesus died “for our sins” or “for the forgiveness of our sins” and how the idea supplies a felicitous Old Testament referent for the multiple New Testament assertions that Jesus’ suffering was predicted in Tanakh.

In summary, according to the writers of the New Testament, Jesus subjected Himself to execution to permanently fulfill the requirement of the Law that animals be slaughtered for the forgiveness of our sins.

Again, none of this is news to me, nor is it likely news to you. “Jesus died for our sins” has, in accordance with its unmistakable scripturality, become (and probably always was) a foundational Christian tenet. But the idea is so deeply, and therefore distantly, foundational that for me, at least, it has become a dogmatic, unexamined cliché whose workings seem inscrutable, barbaric, or both. Why is it the Father required blood to forgive our sins? How is it justice for the death of an innocent to absolve the guilt of the guilty? Why should we retain an idea that smacks of so much ancient ritual paganism? More broadly, and to restate one of my topmost questions, how does the Atonement, so conceived, work?

Ancient readers might have been able to answer these questions intuitively, which may be why the writers of the New Testament don’t offer much in the way of direct explanation of the mechanics of the Atonement. I, on the other hand, a reader of the Bible thousands of years removed from the Passion and another thousand years again from the original Yom Kippur, can neither intuit answers nor quickly infer them from the biblical text. This incomprehension of mine—here, specifically at “Jesus died for my sins,” this failure to grasp the logic of the sacrifice, is probably the single most important motivation for attempting this essay.

So here goes a hypothesis:

Given the connection the writers of the New Testament see between sins, the Crucifixion, and the offerings of Leviticus 4–6 and 16, it seems to me the way to start answering the question of the mechanism by which the slaughter of Jesus deals with sins and guilt is to try first to answer the question of how the slaughter of an animal was supposed to deal with sins and guilt.

My tentative, admittedly unscholarly answer is this: The slaughter of an animal dealt with sins and guilt by serving as a way for the ancient Israelites to make amends with God. In other words, it was an act the Israelites carried out to acknowledge their prior acts of unlove and disloyalty and to substantially reaffirm to themselves and to YHWH how important He was to them and how committed they remained to being faithfully His, thereby providing grounds for Him to forgive them their sins.

Now, this leaning on “amends” as the key to comprehending Israel’s sin and guilt offerings and thus Christ’s offering on the Cross may be mere synonymic clarification of the word translated “atonement,” which, like many religious terms, has acquired an obscuring layer of definitional dust. But in that dusting off, I start to find myself able to accept Leviticus on its own logical terms. Sin and guilt offerings begin to make sense to me in a way that seems to unearth the intuition I posited ancient readers had: Forgiveness of sins sometimes rightly requires amends.

In my non-ancient, post-evangelical context, this intuition needs some defending. Just the other day, in fact, a friend, in an extended aside comprising part of a longer post in our church WhatsApp group about the reality and finality of God’s forgiveness, wrote, “God’s forgiveness is…based solely in his love and nature […] Forgiveness that requires a transaction (such as blood sacrifice) is not forgiveness.” To him, a forgiveness requiring amends is not only not as purely loving as a forgiveness making no such stipulation—it’s also not even forgiveness.

Yet on the contrary, even if for the sake of argument we set aside the blood sacrifices Leviticus explicitly says God dictated as amends leading to forgiveness, Scripture indicates that God’s forgiveness can very well be dependent on things resembling “transactions”:

- confession,

- prayer for forgiveness,

- repentance, and most admonishingly

- our forgiving others.

Each of these preconditions, rather than being at odds with God’s love and nature, are instead quite consonant with it: Requiring confession keeps us from “deceiving ourselves” about our sinfulness (1 John 1:8) and calling God “a liar” (v. 10). Prescribing prayer for forgiveness not only implicitly contains the benefits of prescribing confession, but also compels us to acknowledge our dependence on God. Requiring repentance prompts us to reorient ourselves toward the Way, makes it less likely we continue in bondage to sin, and thus provides some insulation for the injured party against the possibility of future injury. Stipulating we forgive others teaches us about justice and hypocrisy, obliges us to conform to God’s image, leads us to freedom from anger and resentment, and fosters harmonious community.

For God to forgive us without ever enjoining these preconditions would be for Him to withhold from us the above benefits. How loving would that be?

It’s no different with amends. Amends concretize and thereby reinforce our repentance. They embody and thereby communicate our remorse. They illustrate our sense of the gravity of our sin and the dignity of the injured party and thus serve as the sinner’s overture to reconciliation. Even more fundamentally, in the case of YHWH, His requiring amends in response to the people of ancient Israel “doing any of the things which [He]…commanded not to be done” (Leviticus 4:2,13,22,27) taught us what sin is.

Yes, God could forgive humanity without requiring amends. But as a rule, He shouldn’t. If He did, He would risk our moral deformation: We’d be liable to learn that our relationship to Him is cheap and that our actions with respect to Him don’t matter. Since He is our creator and our king, such a false lesson is not only seriously out of touch with reality, draining the meaning from His kingship and opening the door to antinomianism; it’s also likely to cause us, following what we suppose to be His desired pattern, to expect as divinely demanded right a reflexive pardon from fellow humans against whom we’ve sinned. I hope it’s not hard to see that such a sense of cheap absolution is near the root of the continuation of abuse in many evangelical circles. Continual, unqualified amnesty is terrible for perpetrators and victims both.

So, it is God’s “love and nature” that led Him to codify amends—again, my down-to-earth synonym for “atonement”—into ancient Israel’s way of life. He didn’t require amends for His own sake. He required it for theirs.

OK, that’s as far as I got. Sorry about that.

Let me begin this afterword with a synopsis of a would-be complete answer to my original questions in the paragraph below. The links therein combine to lead to every verse I had found, New Testament and Hebrew Bible, that I mentioned near the top of the essay as making what seemed to me unequivocal reference to the Cross and afforded any sense of Its aims or mechanics. Unfortunately, I’m not affording myself time to unpack how, precisely, each of these verses lead to these answers. But I list them to provide evidence that I have tried to synthesize the entire biblical witness on the matter.

Synopsis

According to the Scriptures, Jesus subjected Himself to execution to permanently fulfill the guilt and sin offering portions of the Law5 and thus offer us, without any soft-pedaling of the gravity of sin, liberation from guilt toward God and any further obligation to make morally necessary amends with Him. In turn, the New Testament also indicates Jesus laid down His life to inspire grateful devotion to Him, thereby offering us a second emancipation, this one out of the naturally self-serving and people-pleasing patterns of the world and into adoption as His people in His kingdom, where obedience to Him and the Father, very often taking the form of unglamorous, servant-hearted, sometimes cruciform acts of love for others, is the rule. Finally and relatedly, the Bible indicates Jesus allowed Himself to be killed to establish the basic temporal precondition for His resurrection, a miracle that reinforces our deliverance from one kingdom to the other by neutralizing the fear of death, which is a hindrance to following Him, and validating His status as God’s chosen one, worthy of our utmost allegiance.6 That all of this is a demonstration of God’s love for us, which I define as God’s kind, generous treatment of us as important, is now obvious to me.

Reflections on my synopsis

If the above account of the Cross needs a name, let’s call it the “vicarious amends & transfer of allegiance” account of the Cross.

Now, is my answer as written above sui generis? Not at all. It certainly borrows terms, if not exact concepts, from more conventional theories of the atonement like Christus Victor and ransom, and my emphasis on amends bears some resemblance to satisfaction theory. Also, since I attempted to hew to the scriptural texts, in many ways I’m simply restating what’s there and thus treading conventional interpretive ground. I am no neophile. I do want sexy in addition to biblical, but if I have to choose between the two, I’ll choose the latter.

However, there are a few elements of what came to me that did strike me as novel and that served as the keys to my feeling like I finally “got” it:

- Understanding the atonement sacrifices of Leviticus simply as ways of making amends with God—indeed, understanding “atonement” as nothing more than a fancy synonym for “amends”—opened my eyes to see the justice of those sacrifices, which is unavoidably foundational to a biblical understanding of Jesus’ sacrifice. I could not have seen this without having read the chapters in Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion called “The Question of Justice” and “Anselm Reconsidered for Our Time.” I don’t recall “amends” being called out specifically in those chapters, but Rutledge’s emphasis on the injustice of immunity stuck with me and definitely gave birth, albeit through a long, drawn-out process of cogitation and formulation, to my establishing amends as foundational.

- In my account we have a substitutionary atonement that steers clear of punitive justice, a type of justice which never seemed to gel well with how it seems Jesus acted and spoke about things. Similar in some ways to how the explanatory deployment of the word “amends” is a mere synonymic move, it now seems to me that a non-retributive yet still substitutionary atonement has been staring us in the face the whole time. How many times do we have to read Hebrews before we understand that Jesus was a substitute for the bulls and the goats offered to the Father, not a substitute for us humans punished by the Father?

- That Jesus died specifically to create a people for Himself is not something I remember hearing about in any discussions of the Cross growing up. Maybe it was understood.

- Attestation of Jesus’ messiahship is itself salvific: a concept right there at the top of Romans the whole time, but escaping me until recently because I didn’t understand until recently what a “gospel” was. (Religious jargon, man. Why?)

- Mine is the only account of the Cross of which I’m aware that (1) expressly tried and at least mostly succeeded to take into account every scrap of biblical text that has an unequivocal connection to Jesus’ death, and (2) doesn’t just come up with a laundry list of metaphors.

Hopefully, if the Cross wasn’t “doing it” for you like it wasn’t for me, maybe the above elements can help?

Still, let me restate that overall, my proposal is not a new thing:

- It is a ransom theory, just with the recipient of the ransom being neither God nor Satan, but our minds. (See the below section “A matter of the mind.”).

- Speaking of our minds, if we understand them to be the primary battlefield of, spoils of, or co-victors or Jesus’ victory, my proposal plays very nicely with Christus Victor.

- My proposal is very close to being a satisfaction theory and a governmental theory.

- If you remove the “penal” part, my proposal does center something close to the legal justice emphasized in a penal substitution theory.

- Once my proposal establishes the fundamental reason for Jesus’ sacrifice, it becomes in its second-half emphasis on Jesus’ kingship and our followership a close cousin to the moral exemplar theory.

Grab bag of other remarks

Now, if you can bear it, on to some grossly out-of-sequence, definitely discombobulated other points supporting or adding color to the above thesis that I won’t get to formally argue. I’m certain I’ll lose some cogency in the below. Still, I think there’s enough good in these that it’s worthwhile to include them.

Why all the blood?

Did animals need to die? Isn’t there another way God could have stipulated we make amends for our wrongdoing against Him? Does God like blood or something?

In answer to that last question, no, God does not like blood in any absolute sense. God certainly doesn’t like human sacrifice. And if God doesn’t like the death of the wicked, I tend to think he doesn’t really like the death of innocent animals, either. It’s right that His requiring Jesus’ blood and all that ancient animal blood feel weird to us. (It probably feels weird to us in part because Jesus’ cross was so successful at putting the whole idea to bed.)

However, it’s frequently God’s way in the world to work with what we humans present. Blood sacrifice was a common ancient cultic practice. God went ahead and codified it because it was something that would work toward the purpose of making amends with Him.

All forms of amends other than restitution are arbitrary, anyway.7 Think of a three-year-old trying to make amends. They’re going to do it wrong. They’re going to have weird ideas, like offering you their stuffed animal or drawing you an I’m-sorry picture out of mud. Now go further and think of that three-year-old trying to make amends with you but never having met you in person, as was the case between most ancient Israelites and YHWH! But even if the amends offered by your preschooler were weird, you might accept them anyway. Heck, you might even systematize them.

That’s what YHWH did here. And I mean that: Leviticus reports quite plainly that it is YHWH Himself who institutes the rites of the Day of Atonement, and that it is He again who says, plainly, “it is the blood that makes atonement” (17:11). As the writer of Hebrews summarizes: “According to the Law…without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness” (Hebrews 9:22). I don’t see how you can argue YHWH didn’t codify blood sacrifices without descripturalizing Torah.

And even though amends are arbitrary, it is right that there be some kind of concordance in amplitude between the crime and the amends. Sometimes, in minor offense between human and human, amends can take a mere verbal form: If the sin is a mere slight, then an apology alone is sometimes sufficient. God, too, will sometimes just take an apology. But if the sin is more egregious, the amends should grow somewhat. Big sin requires big acknowledgement. Since God is God, sin against Him is by definition big. And the sins we’re talking about here are the entirety of the sins of Israel, corporate (Leviticus 16) and individual (Leviticus 4–6)—and indeed “the sins of the whole world” (1 John 2:2).

So the blood, even though it’s arbitrary, is fitting in its drama. The last time I read Leviticus, it occurred to me that these priests would have been slaughtering animals all day just to keep up. Picture yourself there. Imagine, assuming you had already internalized the connection between sacrifices and making amends with gods, what witnessing all that butchery would teach you about YHWH’s worth and the gravity of sin. I’m glad bloody amends are over and done with—and I believe God is, too—but bloody amends do communicate.

But God said He didn’t want sacrifices

On the other hand, we do have Jeremiah reporting that YHWH “did not speak…or command…concerning burnt offerings and sacrifices” (Jeremiah 7:22). And the writer of Hebrews says mere verses after his “without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness” that “it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins” (Hebrew 10:4), then proceeds in verse 5 to quote David’s claim that YHWH “didn’t want sacrifice and offering” (Psalm 51:16).

Additionally, we have the following:

- “To love him with all your heart, with all your understanding and with all your strength, and to love your neighbor as yourself is more important than all burnt offerings and sacrifices” (Mark 12:33).

- “But Samuel replied: ‘Does YHWH delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices as much as in obeying YHWH? To obey is better than sacrifice, and to heed is better than the fat of rams’” (1 Samuel 15:22).

- “Sacrifice and offering you did not desire—but my ears you have opened—burnt offerings and sin offerings you did not require” (Psalm 40:6).

- “To do what is right and just is more acceptable to YHWH than sacrifice” (Proverbs 21:3).

- “‘The multitude of your sacrifices– what are they to me?’ says YHWH. ‘I have more than enough of burnt offerings, of rams and the fat of fattened animals; I have no pleasure in the blood of bulls and lambs and goats’” (Isaiah 1:11).

- “‘For I desire loyalty [or mercy] rather than sacrifice, and the knowledge of God rather than burnt offerings’” (Hosea 6:6, quoted by Jesus twice).

In response to people who use the above verses to try to say YHWH never commanded sacrifice in the first place, I have these things to say:

- I’ve already freely—and happily—stated that in an absolute sense, God does not have any intrinsic desire for or pleasure in blood sacrifice. That addresses the Psalm 51 bit. We might say that Jesus’ cross is a way for Him to satisfy the “permanent statute” of the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16:29-30) yet effectively do away with it once for all, thus ending the bloodshed for which He doesn’t really have the taste.

- The bulk of statements above are statements of preference. If forced to choose, God would much rather have obedience in the first place than sin followed by amends. That’s true of any of us in any relationship. In most of the above texts, YHWH was dealing with people who wrongly prioritized going through the motions of compensatory ritual observances over actually doing the more substantial, non-compensatory acts YHWH had told them to do in the first place. This addresses all but the bits from Psalm 40, Jeremiah 7, and Hebrews 10.

- I daresay the Psalm 40 bit is hyperbole.

- For the Hebrews 10 bit, if you read carefully, the writer of Hebrews is making a point about the temporariness of the effect of the blood sacrifices as compared to the permanence of the blood sacrifice of Jesus.

- As for Jeremiah 7, there are clearly overtones of God being sick and tired of His people ignoring obedience and justice and prioritizing cultic practice as in my “statements of preference” reply in number two above. As for the heart of the objection in verse 22 (“I did not speak to your fathers or command them on the day that I brought them out of the land of Egypt, concerning burnt offerings and sacrifices”), it too could be a hyperbolic form of that contrastive preference. But even if it’s not, the statement is literally true according to the text of Exodus: God’s first command of a sacrifice or offering after crossing the Red Sea came some six chapters and an undetermined but significant time later.

So the sacrifices, as a way of amends, are still right and good. They’re just not right and good when they’re mis-prioritized. God prefers non-cultic good deeds every time.

We would do well to remember the above as we consider the role of devotional music, prayer, and financial offerings to the church as part our individual and corporate relationship with God. They are not as important as good works:

With what shall I come to the Lord

And bow myself before the God on high?

Shall I come to Him with burnt offerings,

With yearling calves?Does the Lord take pleasure in thousands of rams,

In ten thousand rivers of oil?

Shall I give Him my firstborn for my wrongdoings,

The fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?He has told you, mortal one, what is good;

And what does the Lord require of you

But to do justice, to love kindness,

And to walk humbly with your God?— Micah 6:6-8

Neither Jew nor Gentile

Moving on to different matters, a corollary, near and dear to Paul, of the fulfillment of the guilt and sin offerings of the Law, itself part Jesus’ wider fulfillment of the whole Law, is that all people, not just Jews, are welcome to join the people of God without any requirement to make ritual observances—not because the Law was abolished, but because it was fulfilled and then justly set aside in favor of a new covenant in the blood of Jesus onto the heart of anyone, Jew or Gentile. This is the conceptual point of Paul’s letter to the Galatians, as well as of much of his letter to the Romans and some of his letter to the Ephesians.

It was such an important point that, in combination with some terribly overgeneralized readings of the gospels that blame “the Jews” for crucifying Jesus, it got inflated and radically distorted so that by the second century AD, it was rabid gentilizing, not judaizing, that was the problem.

Yet the account of the Cross I’m tendering here features much more continuity with and respect for Torah than that. This Christianity is no supersessionism; it’s an expanded Judaism.

A matter of the mind

The saving work of Jesus as I synopsized it above has its direct effect on one thing (or in one place, if you will): Human minds. This aspect of my conclusion first occurred to me while examining 1 Corinthians 15:1-3, where Paul writes that we’re saved “if [we] hold firmly to the word which [he] preached to [us], unless [we] believed in vain.” If the salvific effects of the Cross happened somewhere other than in the Corinthians’ minds, how then could those effects be subject to whether the Corinthians held firmly to what was preached or whether they believed it well? I find reinforcement of this idea in trying to figure out:

- the Romans 1:16 bit I mentioned above, where it’s a gospel—an announcement that is the power of God to save,

- Galatians 5:1-8, where Paul writes, “If you have yourselves circumcised, Christ will be of no benefit to you” and then speaks in term of this as being a “persuasion,” and

- Colossians 1:24, where Paul writes that by his suffering in his flesh for preaching he is “supplementing what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions in behalf of His body, which is the church.”

Wait, what? Something was lacking in Jesus’ sufferings? I thought the Cross was all-sufficient? What on earth could Paul’s sufferings do if the effects of Jesus’ cross were in God, in the devil, or in the cosmos at large? Just a few verses later, Paul tells us what he is talking about, which I read as being basically the same as the “Jesus is Messiah” half my synoptic answer above. Here’s Paul:

For I want you to know how great a struggle I have in your behalf and for those who are at Laodicea, and for all those who have not personally seen my face, that their hearts may be encouraged, having been knit together in love, and that they would attain to all the wealth that comes from the full assurance of understanding, resulting in a true knowledge of God’s mystery, that is, Christ Himself, in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge. I say this so that no one will deceive you with persuasive arguments (Colossians 2:1-4).

Clearly, then, I fall on the side that says the work of the Cross is subjective, not objective, although I doubt the distinction is helpful, and I’m tempted to say the human mind is what the writer of Hebrews has in mind (or at least was referring to unknowingly) in his talk of “the sanctuary” and “true tabernacle” in heaven where Jesus performed His real priestly service.

It also helps answer the question: “OK, if Jesus is paying a manumission fee for us, to whom is He paying it?” The answer is our own minds.

Again, the purpose of the Crucifixion’s attestation of Jesus’ lordship is to change our minds. We once thought: “Jesus is not lord.” But now we think: “Jesus is lord.” And by that we are saved.

Jeremiah 31:31-34 is a scriptural excerpt that didn’t make its way into my attempt at an exhaustive list of scriptures about the work of the Cross, but which seems to come pretty close to restating my synopsis of the work of the Cross and pointing to the human mind as its locus:

“Behold, days are coming,” declares the Lord, “when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah, not like the covenant which I made with their fathers on the day I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt, My covenant which they broke, although I was a husband to them,” declares the Lord. “For this is the covenant which I will make with the house of Israel after those days,” declares the Lord: “I will put My law within them and write it on their heart; and I will be their God, and they shall be My people. They will not teach again, each one his neighbor and each one his brother, saying, ‘Know the Lord,’ for they will all know Me, from the least of them to the greatest of them,” declares the Lord, “for I will forgive their wrongdoing, and their sin I will no longer remember.”

Knowing that the saving effects of the Cross occur in our minds helps me understand how come the Crucifixion doesn’t appear to work those effects automatically. Those effects are subject to whether we accurately apprehend and believe them. Jesus’ dying doesn’t automatically liberate me from the fear of death. It is conceptual. You have to “eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood” (John 6:52-58) to have life.

Eucharist (literally, “thanksgiving”)

Speaking of eating Jesus’ flesh and drinking His blood, I think I finally understand communion. Attending an Anglican church service while visiting Bergen, Norway this past March helped a lot. There, I witnessed and partook of the Eucharist, as they call it, presented in a certain, formalized way: We each came to the front of the church, kneeled around an altar as there was room, and held out both hands open and upward. The priest or a deaconess placed a wafer in our hands, said, “the body of Christ, broken for you,” and we ate. Then the priest or a deacon gave each of us a sip of the chalice wine, saying, “the blood of Christ, shed for you” as we sipped. After each of us had had our turn, the deaconess and the priest took turns kneeling before each other and doing the same.

Witnessing and participating in this is probably old hat if you’re Roman Catholic, Anglican, or Orthodox. But for this low-church Protestant, all the kneeling and the open hands along with the inclusion of the deaconess and the priest as kneelers hammered home for me that communion / the Lord’s supper / the Eucharist is meant to be received as a gift reminding us of the work of the Cross, not as some self-administered wake. Since the salvific work of the Cross is noetic and affective, this heartfelt reminder that I am a sinner, that Jesus graciously provided a way for me to make amends with the Father, and that I do best to incorporate His life into my own by “eating His body” and “drinking His blood” is as good as being saved all over again if I will only see it that way! I’ll gladly do this every week now that the sacrifice makes sense. If I fully digest the Lord’s supper, I am more likely to gratefully “do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly with my God” (Micah 6:8), including a readiness to do the hard work of making amends with the people against whom I’ve sinned.

In summary, our participation in the Eucharist is a way of claiming the sacrifice of Jesus as our way of making amends with God, and it serves as a conceptual door to participating in the life of Christ’s kingdom.

How is Jesus offering His life a way of us making amends?

In a way, it’s not. But then, neither was us offering bulls and goats. After all, God owns the cattle on a thousand hills. It’s impossible to give Him anything other than intangible, relational goods like fidelity and obedience, which is really what He is interested in in the first place.

But we do need some way to acknowledge our prior acts of unlove and disloyalty and to substantially reaffirm to ourselves and to YHWH how important He is to us and how committed we remain to being faithfully His. By confessing our sins and appealing to the sacrifice of Jesus, freely offered on our behalf, fully acknowledging the weight of sin and the magnitude of the gift, it is enough. It helps that Jesus is human and that He was perfect. (The differences, by the way, between forbidden human sacrifice and the sacrifice of Jesus are that He offered Himself and that He had a promise that His death would be temporary.)

It’s the perfect marriage of justice and mercy, with mercy given the slight edge: The Father’s acceptance of Christ’s cross as our amends is just in that it accords with the gravity of our sin and still requires our offering Him our fealty to be valid, but it is very merciful in that we are not actually the ones to offer it.

Various smaller, half-coherent notes

- It was reading 1 Timothy 2:6 that prompted me to structure my synoptic account of the Cross as a twofold manumission.

- I take “the testimony given at the proper time” in that same verse to mean, “Just in time for God or the Romans to tear down the Temple and put an end to the Jewish sacrificial system.”

- The guilt and sin offerings and the Cross are not mere metaphor, not just performance art, and not only cultural accommodation. They are actual amends offered to God.

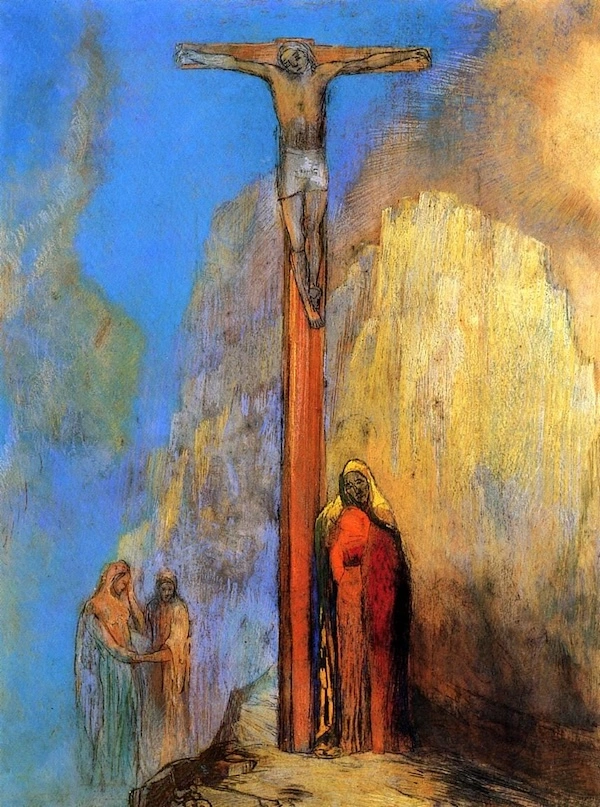

- Even though Jesus is alive, crucifixes are superior to empty crosses as Christian symbols because they remind us more saliently of Jesus’ sacrifice and of His Way. Keeping Christ on the Cross is precisely what Paul meant when he wrote in 1 Corinthians 1:17, “For Christ [sent] me […] to […] preach the gospel, not with cleverness of speech, so that the cross of Christ would not be made of no effect”—literally, “so that the cross of Christ would not be emptied,” a much better translation given the primary thrust of Paul’s letter, which appears to be correcting haughty, super-spiritual men acting in very un-cruciform ways, and given how easy it is for me to see that cleverness of speech is antithetical to the self-execution on display on the Cross). We follow Christ crucified.

- There are elements of a moral exemplar theory of the atonement in my synoptic answer, but only after we establish that the primary reason for Jesus’ self-sacrifice. Without the Cross having some primary effect, the Jesus of the moral exemplar theory of the atonement is just like my brother in the simile at the beginning of the essay, jumping in front a train “for my sake” but for no apparent reason. It’s not loving to surrender your life for no good reason.

- If you don’t yet grasp the guilt-and-sin-offering part of my answer, I encourage you to keep digging. It’s a deep well, and once you hit water, you’ll find it very life-giving.

- I want to emphasize something I merely mentioned in the essay: The sin Jesus directly addressed via the Cross was our sin against God—not our sin against one another. God cannot forgive us for sin against others except insofar as a sin against His creation is a sin against Him. I’ve touched on this elsewhere. This idea is very familiar to Jews. “For transgressions between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones; however, for transgressions between a person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person” (Mishnah Yoma 8:9 as quoted by Sara Himeles). Chalk some Christians forgetting this up to enthusiastic over-generalization. (We’re good at that, apparently.)

- “[Jesus] endured the cross…for the sake of the joy that was laid out in front of him“ (Hebrews 12:2). Jesus did this because He wanted to for joy. My reconciliation to the Creator was His joy. That touches me.

- No more ritual observances (other than baptism and Eucharist, which are not primary but rather reflective); no more guilt before God for all who confess their sin (the sinner beating his chest); no more fear of death; and a clear way forward: the way of the Cross. In summary, a whole way of thinking has been crucified by the Crucifixion of the Christ and replaced with something new.

Unanswered questions

- How does Jesus’ cross reconcile all things to the Father like it says in Colossians 1:19-20? The “things on earth” part I can ascribe to our role as stewards on earth, making our reconciliation to the Father entail the reconciliation of terrestrial creation, but that doesn’t explain the “things in heaven” part. Maybe the “things in heaven” part has to do with worldviews and spirits of the age—the “spiritual forces of wickedness in the heavenly places” Paul writes about in Ephesians 6.

That’s all I’ve got to say. Thanks to everyone who permitted me to think out loud with them and who offered examining questions as I slogged through this stuff. Thanks to my wife who permitted me to spend hours in front of the computer, sometimes writing as little as a sentence an hour, without complaint. And thanks to God the Father and His perfectly loving Son, whose reasons for getting Himself killed finally make sense.

1 For a similar illustration, see also the highlighted paragraph beginning “Similarly I would agree that an understanding of the cross” in Derek Flood’s 2006 blog post “Subjective and Objective Atonement - Abelard,Girard.”

2 Or, at my best, clinging desperately to what small truths about it that I can wrap my head around, like that Jesus’ crucifixion shows us that God is humble and how Jesus’ crucifixion shows us He can sympathize with our suffering.

3 I will admit that this third way is less than convincing to me, since the relevant Old Testament scriptural references the New Testament makes are either without easily discernible referents, as in Mark 14:48-49, Acts 13:26-29 & 26:22-23, and 1 Corinthians 15:1-4, or baldly eisegetical, as in John 13:18-19, 15:25, 19:24 & 19:36, and Acts 4:24-30. I’m more inclined to read these references, along with all similar NT references not dealing specifically with the Crucifixion, as essentially restatements of Jesus’ claim to messiahship rather than actual evidence substantiating the claim. Hope-filled, confident restatements, for sure, but nonetheless devotionally figural readings rather than actual corroboration. These readings may have carried some persuasive power with their original audience about Jesus’ messiahship by the charm of their consonance with the overall themes of the story and writings of Israel. And I have no trouble choosing to see divine design in some of these figurations. But I see very few, if any, a-ha! OT-NT prediction-fulfillment pairs.

Now, that’s not me saying that some of these figurations aren’t instructive. On the contrary, some of them point to what may be the core component of the answer to my questions, as I think we’ll see later when I turn my attention to Leviticus 16 and Isaiah 53.

4 I predict we will return to elaborate on both these reasons as this essay progresses.

5 Leviticus 4:13-6:7; Isaiah 53; Matthew 26:27-28,42,54,27:51; Mark 14:22-24,35-36, 15:38; Luke 22:19-20, 23:45, 24:25-27, 24:46-47; John 6:52-58; Acts 5:31; Romans 3:21-26, 4:25, 5:6-11, 5:18-19, 6:10, 8:3-4; 1 Corinthians 11:23-26, 15:1-4; 2 Corinthians 5:21 // Galatians 2:20-21, 3:13-14, 5:11; Ephesians 1:7-8, 2:11-16, 5:25-26; Colossians 1:14, 1:19-23, 2:11-15; Titus 2:14; Hebrews 7:27; 9:12-16, 9:23-28, 10:10, 10:19-21, 13:11-14; 1 Peter 1:18-21, 3:18; 1 John 1:7; Revelation 1:5

6 Matthew 12:39, 16:4, 16:21-23, 27:45-54; Mark 8:31-33, 14:48-49, 15:33-38; Luke 9:22, 11:29-30, 17:25, 24:7, 24:25-27, 24:46-47; John 2:18-21, 3:14-16, 8:28, 11:49-52, 12:32, 13:18-19, 14:29-31, 18:32 // Acts 2:22-36, 3:13-15, 4:8-11, 5:29-32, 10:39-42, 13:28-37, 17:3, 26:22-23; Philippians 2:9-11

7 It’s good thing God doesn’t require restitution for our sin against Him, because if He did, we’d be up against a category mistake and thus an impossibility: Since all things are from God, through God, in God, for God, and to God, He can neither suffer material loss or injury nor be given anything material to begin with. When the Offended is wholly self-sufficient, no material amends are possible. I qualify the above with the word “material” because God’s aseity does not entail His feelings cannot be hurt. The prophets and Ephesians are clear that God can be and has been “hurt,” “wearied,” and “grieved.” Accordingly, what God really wants from us is not direct, material sacrifices, but rather intangible, relational goods of fidelity and obedience (1 Samuel 15:22-23, Psalm 40:6-8, Isaiah 1:10-17, Jeremiah 6:19-20, Jeremiah 7:22-24, Micah 6:6-8, Hosea 6:4-11, Matthew 9:10-13, Matthew 12:1-7, Mark 12:28-34), along with true, heartfelt repentance when we fail to bring that (Psalm 51:16-17).