His Cross is not a coat of arms. It’s a teacher, a master, a goad.

Screen addiction, which I define much more broadly than the APA might, is harmful for the same reason suicide is harmful (and thus called by many religious people a sin): It removes people, with all the skills, humor, and other virtues they might bring to bear on the world, from the social nexus and destroys human attachments. It is a hermitage.

Just finished reading: “Contemplation as Rebellion: The case for unenchantment” (2025) by Nicholas Carr, whose main ideas are that to patiently, contemplatively attend to things is to engage ourselves and our world in the best way—especially contra a society rife with stimulation and mere perception. And it has nothing to with “enchanting” anything.

Just finished reading: “From Dietrich Bonhoeffer to James Cone: The complexities of forgiveness in a racialized Society” (2024) by Reggie Williams, whose main idea is that in America, Black forgiveness is a maintainer of the status quo.

Some striking quotations:

- “Can forgiveness find a footing in broader systemic realities?”

- “To encourage [Black people] to see their suffering as righteous obedience to God in Christ is to sanctify a perpetual social death.”

- “In a moment of racial distress, forgiveness becomes a reflex response that serves the social maintenance of racial hierarchy.”

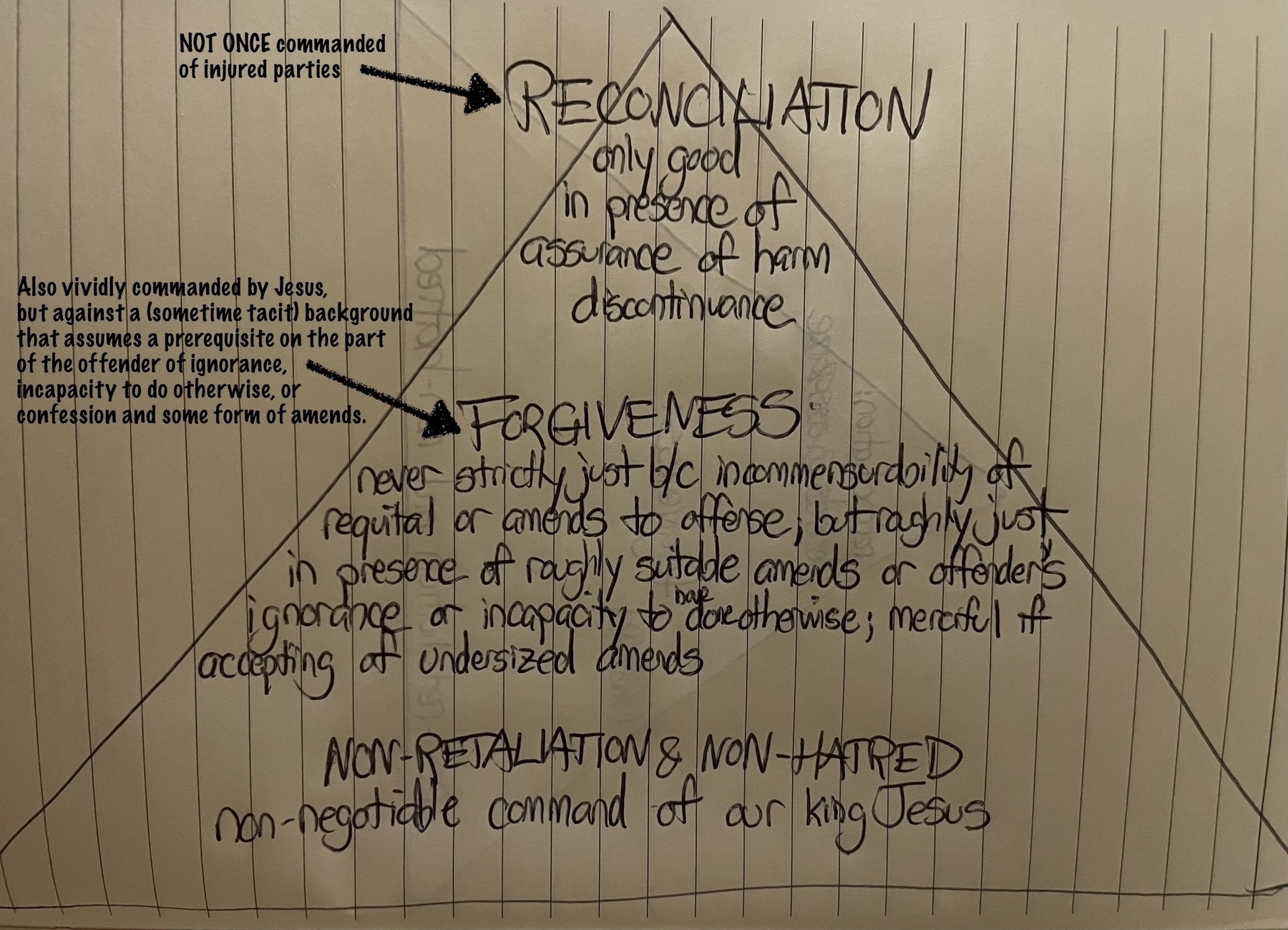

Some quick reflections: This is why forgiveness without amends is usually bad.

Potts is right that punishment and recompense will always be incommensurate with the wrongdoing (except for restitution, which can come close). That’s how you can say that forgiveness and justice can and do coexist: Forgiveness doesn’t say nothing is due; forgiveness says that what’s been paid is enough. Nothing more is due.

Just finished reading: “Forgiveness ≠ Reconciliation: Wisdom for Difficult Relationships” (2024) by Yana Jenay Conner, whose main idea is well summarized by the title. This was my favorite article in the Winter 2024 issue of Comment. Conner helped me realize that Matthew 18 contains a righteous unforgiveness: “And if he refuses to listen…let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector" (v. 17). And these two partial quotations struck me as beautiful: “I was a daddy’s girl without a dad…” and “Even if I was interested in adjusting my grip on the cross…”

Just finished reading: “Promise, Gift, Command: Mapping the Theological Terrain of Forgiveness” (2024) by Brad East, who main ideas can’t really be summarized but can be itemized. According to East, forgiveness is:

- from God [meaningless],

- peculiarly Christian [false],

- integral to but not the whole of the gospel [agreed],

- administered by the sacraments [false],

- tricky [can be, but not as a rule],

- when we extend it, evidence that we have been forgiven ourselves [can be, but not as a rule], and

- something about which he still has several important questions [good, because he is muddled and hasn’t written a cogent essay here].

Just finished reading: “Out of the Depths: How Forgiveness Brought a Sex Offender Into the Light” by a man who fell and “Into the Depths: The cost of forgiveness will be your life” (2024) by a wife who forgave.

The man who fell submits that both easy acceptance and permanent excommunication are not good, the former creating dysfunctional communities by ignoring the woulds of the aggrieved, and the latter destroying the sinner. (For my part, I’ll add that the latter also creates dysfunctional communities.) His wife forgave him, doing neither of the above. And by that, he was saved. It even elicited repentance, he says.

The wife who forgave says she forgave he husband, and it has cost her a lot. But it’s the way of Christ, and it, she says, has made her holy.

Just finished reading: ”New Eyes: Forgiveness is not erasing” (2024) by Amy Low, whose main idea is that there is danger that forgiveness will unjustly erase the past. There is also a danger that unforgiveness will spoil potential futures for aggrieved and offender alike. Let us avoid both ditches as we walk the path.

“Go, eat delicacies and drink sweet drinks and send portions to whoever has none prepared, for the day is holy to our master, and do not be sad, for the rejoicing of YHWH is your strength” (Nehemiah 8:10, Alters). The enjoinment to enjoyment along with generosity, both in the name of the Lord, warms my soul.

I finally feel comfortable with my grasp of the relationship between non-retaliation, forgiveness, and reconciliation, together with God’s will regarding all three:

Mercy can be unwise.

Mercy is by definition unjust.

Just finished reading “Die With Me: Jesus, Pickton, and Me” (2006) by Brita Miko, who argues that we need to love and forgive even the worst of sinners if we’re going to follow Jesus. My take: Not if you think forgiveness should be granted without confession and repentance, as it seems Miko does.

“There is no escaping the fact that want of sympathy condemns us to a corresponding stupidity.”

— George Eliot • Daniel Deronda (1876)

May all of our eros be agapified.

To insist it is my civic duty to read about, think about, and talk about tyrants only augments their tyranny. Ignoring tyrants is my preferred mode of protest. NB: This is not the same as saying I will ignore the effects their tyranny has on my neighbors.

The degree to which you don’t buy the fundamental idea I put forward in this essay that amends are necessary for a just forgiveness is the degree to which you can stand even more amazed at the love of Jesus in subjecting Himself to crucifixion to provide that (proxy) amends. You may not believe amends are necessary for forgiveness (and if you don’t, that itself may be an indication of Jesus’ ideological success), but Jesus’ contemporaries and forbears did think so. If the idea is mere cultural contingency rather than ethical fact, that only makes Jesus’ sacrifice all the more amazing in its condescension—and thus more apt as reason to sit at His feet and align yourself with His overall ethical program.

Some introspection while walking home from a nighttime walk with Matt after an evening when I failed miserably to bring together a cohesive Spring Break plan for the family:

Too often at home and at church and, historically at least, at work, I stand opposed to and suspicious of what’s being brought by others. Blame eighteen years as an academic. (I’m using that term very loosely to include K-12 and undergraduate.) Blame a natural bent of my mind.

But that’s not what’s gonna get it done. When I say “it,” I mean togetherness, I mean unity of vision and will. I mean a sense of belonging and cherishing. I mean laughter.

No, what I need if I want those things at my kitchen table, in church, and at work is the “Yes! And…” spirit of improv. Bring myself and what I have to offer in a positive sense, sure—and honor that which others bring of themselves. “Yes, that’s right! And we can do this…” That’s so good. That’s the way.

“But to have spoken once is a tyrannous reason for speaking again.”

— George Eliot • Daniel Deronda (1876)

“Should” is a word with real, live uses

Granted, it’s seen its share of abuses ✏️ 🎤 🎵

Part of 1 Corinthians 16 is as a good a motto as one can find: “Do everything in love.” Since so much of my life comprises words, and since the biblical proverbialists, Jesus, and James all emphasize the power and importance of our words, I’m going to provisionally subset the motto to concentrate its effect: “Say everything in love.”

Cheerful, curious, grateful, harmonious, sympathetic, brotherly, humble. That’s what I want to be.

The word of the year this year is “get to”: Everything I do, I get to do. (Hat tip: Ethan.)

This is what self-exhortation (in this case, to be a better listener) sometimes sounds like in my house.

“If you find honey, eat just what you need, lest you have your fill of it and throw it up” (Proverbs 25:16). Anything, even very pleasant things like musicmaking or music listening, can become noxious if too much.